Saba, 14, loves learning languages — especially French and English — even though French isn’t taught at her current school. Born in Sudan, Saba now attends school in a refugee camp in Farchana, Chad — where her family has sought refuge for nearly two years. She already excels at Arabic and is eager to learn more so she can forge connections beyond her own community. “When we talk directly,” she says, “we can help and can really understand each other.”

“We suffered a lot in our war,” Saba continues, “and we don’t want others to suffer. We are going to help those who come behind us. We want the war to stop. We don’t want children to be born here to see the war continue.”

Saba and her classmates volunteer to answer their teacher’s question.

Nurturing minds and bodies at school

In Farchana refugee camp, schools play a vital role in helping displaced children continue their education, regain a sense of normalcy, and meet their physical needs. Through school feeding programs here and throughout Chad, World Vision helps provide children what might be their only meal of the day — and some students share the food with the rest of their family. Each day, when Saba, her brother, and their two cousins return from class, they bring their school meal home. Together, the four children split their portions between 10 people.

Saba’s mother, Zoulaikha, teaches physics at a nearby secondary school. “My mother is my role model because she thinks of us most,” says Saba. “She does her best to support us. What she earns isn’t enough, but she does her best to take care of us … if we need anything, she tries.”

Zoulaikha carries the weight of both parenting and provision. “I will always do my best to meet their needs … I try to cover the distance and lack of their father by my side.” She’s a single parent with two of her three children attending school within the refugee camp. World Vision’s school feeding program helps her stretch what little they have. Back in Sudan, her family ate three meals a day. Now, they manage with two. “Before with no food, I pushed them to go to school, and now they desire to go without pushing.” Now, school is a place where they nourish their minds, bodies, and dreams for their futures.

El Geneina under fire

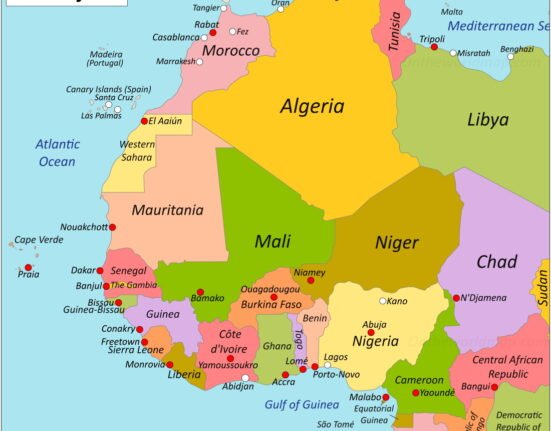

Before they fled to Chad in June 2023, Saba and her family called El Geneina, Sudan, home. Zoulaikha worked as an accountant for the financial ministry. Their family was together, their income steady, and there was always enough food to go around.

“We used to live a comfortable life,” says her grandmother, Sadia. “We were not suffering. I sold spices and cucumbers and onions. We could cover all of our needs.”

But when conflict escalated, everything changed.

In June 2023, their town came under attack. The streets were filled with gunfire, and their home, once a place of security, was no longer safe. “I wanted to save my children,” says Zoulaikha. “They were afraid and there were loud gun noises. We suffered along the way.”

Saba’s father remained behind. “He said, ‘I was born here — this is my home. I was born here, and I will die here,’” recalls Zoulaikha.

They haven’t heard from him since.

Before they left, their neighbors — people they loved — were also killed.

“We were inside rooms, and they shot at us like rain,” Sadia recalls. The killings were relentless. On the first day, she says, they saw 50 people die, and on the next, 92 more.

Eventually, their family was able to flee toward Chad, walking for hours until someone picked them up. Along the way, they were attacked again.

“They shot at us,” says Zoulaikha. “They looted everything — our telephone, money, and dates.” Without communication, funds, or food, they carried on.

When they finally crossed the border, the silence was a relief. “When we crossed, there were no guns, no shooting,” she says. “We said, ‘Praises.’”

A portrait of Sadia, Saba’s grandmother.

Suffering in silence

But silence doesn’t heal scars, and the trauma of conflict does not end at the border. For families like Saba’s, the memories of gunfire, loss, and fear linger.

“We are psychologically scarred,” says Zoulaikha. “There’s mental health support in the camps. It helps, but it’s not enough.” She experiences horrific nightmares reliving her trauma again and again. She says they need material help to rebuild their lives, but addressing the emotional toll of what they’ve endured is just as important. “We need development, but our minds are also suffering.”

She hears children whisper to each other about what they endured on their way to Chad. “The children talk between themselves,” she says. “They ask if this war is going to happen again.” But she struggles to find the emotional capacity to talk to them about it. “Because they’re Sudanese, and I don’t want them to endure it again. I hate it. And I don’t want them to suffer again.”

Casting a vision for tomorrow

Looking ahead, Zoulaikha hopes education will offer her children something conflict has threatened to take away. “For my tomorrow, I want to live in a safe environment and [have] education for children … I worry about their future. I don’t want to stay here. They stopped their education when the conflict began. And if they stop, they lose,” she says. “Then even if something happens to me, if they’re educated, then they still can have a future.”

At school, Saba sharpens her language skills. She practices English in class and pursues her dream of becoming a flight engineer — a dream she’s held on to since she was 10. Her mother encourages her children to keep learning as she works to support them.

Food, too, shapes what’s possible. School meals have helped keep children in school. “For my children, it’s a big benefit. They stay and eat,” says Zoulaikha. Before World Vision’s feeding program began, many students, including Saba, would go home to eat, only to find no food or parents present. Often, they wouldn’t return, missing out on their education.

“School feeding is good. The rice and beans are rich,” says Saba, “When we eat, we’re full and can spend hours without hunger.”

Despite everything, Saba continues to believe in language. In understanding. And she dares to imagine a future where children will never have to flee — and where those who already have endured trauma can recover and thrive.

Source: https://www.worldvision.org/

Leave feedback about this